[Reposted from Quora Spaces.]

One of the ironies of English history is that the landmark 1689 Bill of Rights, with its prohibition of “cruel and unusual” punishment, was prompted, in part, by the ill-treatment of one of the great villains of the seventeenth century.

In 1678, for want of anything better to do, Titus Oates, a failed student of Cambridge University who conned his way into the priesthood, conspired together with a fanatical – and quite possibly clinically insane – clergyman called Israel Tonge to accuse English Jesuits of a plot to kill the king, Charles II.

They did this totally off the top of their heads, with no basis in fact whatsoever but, given the climate of the times, they were widely believed. The instruction to kill Charles, it was asserted, had come from the pope himself, and so the so-called plot came to be known as the Popish Plot.

As it happened, a strongly Protestant Member of Parliament, by the name of Edmund Berry Godfrey, was murdered shortly afterwards, and Oates seized on this as evidence that his pipe-dream of a plot was true. The press jumped on board and pretty soon a witch hunt of Catholics was under way.

This May 1679 issue of The London Gazette denounces the “Bloody and Jesuitical Principles” underlying another murder, that of James Sharp, the Archbishop of St. Andrews in Scotland. The true culprits turned out to be Presbyterians.

The country was in the grip of anti-Catholic hysteria. Following Godfrey’s murder, Catholics were banished from London and were not permitted within a 20-mile radius (later reduced to 10 miles) of the city. Several others (prominent among whom were Stephen Dugdale, Robert Jenison and Edward Turberville) jumped onto the bandwagon, and started accusing Catholics willy-nilly.

At least twenty-two Catholics were put to death, others died in grossly inhumane conditions in prison, and still others were killed by mobs.

Finally, Oates was exposed and it was acknowledged that there was not, and had never been, any such plot. A fat lot of good that did to the Catholics who had died, though, and the ban on Catholics (other than tradesmen and householders) entering London was maintained. Although Charles II himself was bitter about the number of people whose execution he had authorized as a result of the deception, anti-Catholic prejudice continued unabated, and scant remorse for the injustices done was expressed by the press or the populace at large.

Which is why I call it an irony that the Bill of Rights of 1689 was partly inspired by the punishment that Oates received. Make no mistake, he paid a high price. When James II, who had converted to Catholicism, came to the throne in 1785 he had Oates thrown in prison and sentenced to be whipped through the streets five days a year for the rest of his life. The presiding judge was Judge Jeffreys, “the Hanging Judge”, and it’s speculated that the aim was for the whippings to kill Oates, since Jeffreys could not impose the death penalty for perjury.

The irony is that, while remaining apparently unmoved by the executions, banishment from the capital and general mistreatment of Catholics, the public reacted strongly to the punishment meted out to Oates, the cause of all this suffering. John Phillips, for example, was outraged at “Protestant Judges condemning a Protestant, and the Detector of a most Horrid Popish Plot” (The Secret History of the Reigns of K. Charles II and K. James II [London, 1690], p. 187), impervious to the fact that the “horrid” plot he refers to was a complete fake.

The Bill of rights of 1689 was designed to prevent judges from overstepping the limits of their powers and inflicting punishments that went beyond their mandate.

A Remonstrance of Innocence, published in 1683, is a Catholic account of the deaths of those executed for their supposed involvement in the fake plot.

When James II was ousted, in 1689, Oates was pardoned, released from prison and given a pension. He died in relative obscurity in 1705.

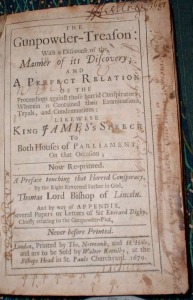

- The two illustrations to this post are from my collection of early modern publications. I’ve written a bit more about them and the context in which they were written here: Religious Controversy: POPISH PLOT.

- For further details on Oates and the Poposh Plot, see Susan Abernethy’s informative blog post: Titus Oates.